When

the poster advertised ‘High Tea with Dickens,’ celebrating the author’s

birthday, I expected a few pots of hot water and a discussion. But I

was mistaken. They were serious about the high tea, and Lang Cafe

boasted a sumptuous spread: different types of teas, cheeses, fruits and

vegetables, breads and spreads, and even chocolate biscuits. Toothpicks

stood in little cups to facilitate retrieval of tea bags, cucumber

slices and crumbly chunks of cheese. I happily filled my plate and cup.

Associate

Professor of Literature Carolyn Berman presented a talk on ‘Dickens and

the Art of Representation,’ which I found more palatable than the food

(even the chocolate biscuits). Berman studies 18th and 19th century

fiction and is currently working on a book on Dickens, Parliament and

the media. The text and images she showed us connected lightly with the

research for this book, but are not a part of her manuscript.

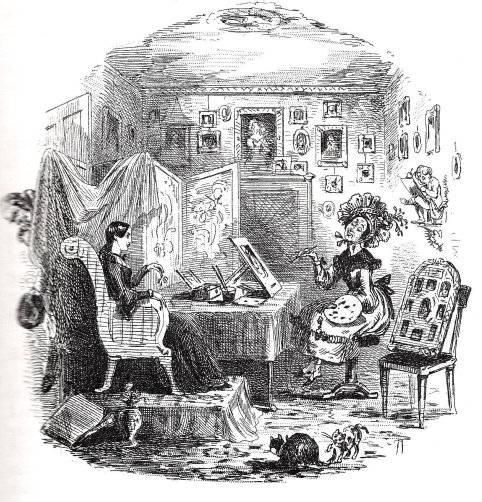

To open a discussion about representation, Berman started with images. She showed us an illustration from Nicholas Nickleby,

of Miss La Creevy painting a miniature portrait of Kate Nickleby. As

you can see, Miss La Creevy is depicted almost larger-than-life, with an

enormous hat, elaborate outfit, and surrounded by her paintings, making

very clear to the reader that Miss La Creevy is a painter. The details

of the image are inaccurate--one did not use a paintbrush for

miniatures, for example--but Dickens and the illustrator were more

interested in the representation of the characters by their

accoutrements and descriptive characteristics. In fact, Miss La Creevy

later describes the difficulty of miniature painting, since heads have

to be enlarged, eyes widened, noses diminished and teeth invisible. Cut

to a miniature portrait of Dickens when he was 18 years old, painted by

his aunt, and those techniques are apparent. At the time that Dickens

was writing, stories were printed in installments in publications, and

generously illustrated. This allowed for conscious and unconscious

collaborations between the writer and illustrator, where prose tried to

approximate image, and vice versa. Characters, therefore, came into

existence flush with adjectives and accessories, their representation

confirmed and compounded by each other.

To open a discussion about representation, Berman started with images. She showed us an illustration from Nicholas Nickleby,

of Miss La Creevy painting a miniature portrait of Kate Nickleby. As

you can see, Miss La Creevy is depicted almost larger-than-life, with an

enormous hat, elaborate outfit, and surrounded by her paintings, making

very clear to the reader that Miss La Creevy is a painter. The details

of the image are inaccurate--one did not use a paintbrush for

miniatures, for example--but Dickens and the illustrator were more

interested in the representation of the characters by their

accoutrements and descriptive characteristics. In fact, Miss La Creevy

later describes the difficulty of miniature painting, since heads have

to be enlarged, eyes widened, noses diminished and teeth invisible. Cut

to a miniature portrait of Dickens when he was 18 years old, painted by

his aunt, and those techniques are apparent. At the time that Dickens

was writing, stories were printed in installments in publications, and

generously illustrated. This allowed for conscious and unconscious

collaborations between the writer and illustrator, where prose tried to

approximate image, and vice versa. Characters, therefore, came into

existence flush with adjectives and accessories, their representation

confirmed and compounded by each other.From there Berman moved to textual representations of characters -- the bit I found most interesting.

She read aloud the second and third paragraph of the first chapter of Great Expectations:

“As I never saw my father or my mother, and never saw any likeness of either of them (for their days were long before the days of photographs), my first fancies regarding what they were like were unreasonably derived from their tombstones. The shape of the letters on my father's, gave me an odd idea that he was a square, stout, dark man, with curly black hair. From the character and turn of the inscription, "Also Georgiana Wife of the Above," I drew a childish conclusion that my mother was freckled and sickly.”

Young

Pip probably could not read at this time, and yet he drew information

from text, from letters, about his parents -- that we, as readers,

similarly were drawing from to learn about the characters. Berman

pointed out the refraction of information and experience here: where

illiterate Pip is responding to the appearance of the words, the

lettering on the tombstone, we are fully literate and converting Pip’s

intuitive reactions into realities for his parents’ characters. Dickens

found unconventional ways to represent characters to other characters,

and, one layer later, to us.

“At such a time I found out for certain that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip.”

Berman

marveled at this passage for a few reasons: it being a confident run-on

sentence, Dickens’ deferral of the subject (Pip) until the very last

word of the last line. I enjoyed it for the wording: I can imagine a

long quiet river being a “low leaden line” and the source of the wind,

yet unexplored by a young character, being a “distant savage lair.”

Berman

marveled at this passage for a few reasons: it being a confident run-on

sentence, Dickens’ deferral of the subject (Pip) until the very last

word of the last line. I enjoyed it for the wording: I can imagine a

long quiet river being a “low leaden line” and the source of the wind,

yet unexplored by a young character, being a “distant savage lair.” Dickens learned shorthand to become a Parliament reporter. His fascination with graphic representations continued as he imagined the ‘arbitrary characters’ of Gurney’s Shorthand as arbitrary characters in his works, playing with the words, the implications, and the characters themselves.

For a man whose vocation was words, art was never far from his mind.