Readers often

confuse fiction for non-fiction and vice versa, with narrators resembling

authors, fictional characters resembling real ones and real lives being

story-fied. So how does one categorize a book that explores a country of one billion

people by following five principal characters, a book whose first person

narrative is not explicitly the author’s voice?

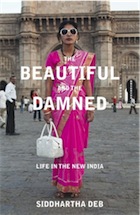

We settle into

our chairs to listen to Siddhartha Deb read from such a book, his latest work, The Beautiful and the Damned: A Portrait of

New India, to try to answer these questions.

We settle into

our chairs to listen to Siddhartha Deb read from such a book, his latest work, The Beautiful and the Damned: A Portrait of

New India, to try to answer these questions.

Deb does not

preface his reading with much context, although book includes a touching

Introduction about struggling with his slippery north-eastern Indian identity while

growing up, “resident of the land that my father had left and that I had never

lived in.” Today, he provides a bit of background about each passage he will

read from, letting the prose take over from there.

And he does,

with flair, turning the pages with the flourish of a piano player. Each excerpt

is dramatized as Deb reads slowly, pausing, smiling and inflecting to give us a

sense his exhausting and revealing travels throughout India:

Vijay brought his tiny car to a halt, and the man loomed up in front of the windscreen, a dark, stocky figure dressed in a T-shirt and jeans. He put his right hand down on the bonnet of our car. In his left hand, he held an automatic pistol, its barrel pointing up at an acute angle. His gaze, as it swept over our faces, was intense, scrutinizing us carefully, meeting our eyes for a few seconds.

Deb frequently

takes his eyes off the page to look straight at us and off to the side, and his

familiarity with the text makes his reading that much personal, the pistol that

much more tangible. Describing this police checkpoint on a highway out of

Hyderabad that Deb had driven on, he points out to us that not only was it

illegal, it was also in vain. His writing renders this impromptu call to action

utterly impotent in an impassive scene of oozing traffic and sense-numbing smog.

“The ‘I’ in the

book is not a journalist ‘I’. It’s more a narrator ‘I’ who has a history, has

memories,” he says. A combination that gives his characters histories and

memories, too, such as the wife of one of the few wealthy farmers in rural

Andhra Pradesh:

My attention was drawn to the woman in her thirties, everything about whom suggested that she was the mistress of the house. She was wearing a bright blue sari, from the fringes of which one foot displayed a gleaming golden toe ring. She was slightly plump, and light-skinned – attributes that declared the upward mobility of the man who had married her with as much clarity as the marble and teak fittings of the house.

Deb remarks a

paragraph later that this woman does not seem fazed by the charred, dusty state

of her house—recently set on fire by angry famers cheated out of their revenue

by her husband—nor by her husband’s feckless behavior. The way she carries

herself reflects her standing: a woman of higher social class than the farmers

in the town, a woman with property, a woman with status and promise.

Less classily

portrayed is the infamous and now defamed personality, Arindam Chaudhuri.

People told Deb that he seemed “grotesquely fascinated” with Chaudhuri, that he

explored—and exploited?—Chaudhuri’s life more critically than he did other

characters in the book. Why? Deb argues that he took much care to respect the

privacy of his characters, omitting details and changing names when asked.

Chaudhuri, however, was already a grandiose figure in India, notoriously

ubiquitous, dominating print advertisements and amplifying his voice to the

masses. Such a persona could not expect already public information about him to

be disguised for the sake of a book.

Deb boldly depicts

Chaudhuri as the meretricious scammer that he is, sneaking snippets into his

writing that wonder about his unexpected popularity and influence:

The mannerisms gave Arindam an everyday appeal, and it was the juxtaposition of this homeliness with his wealth, success and glamour that created a hold over the leadership aspirants in the audience…He was one of the audience, even if he represented the final stage in the evolution of the petite bourgeoisie…after about thirty minutes into the leadership session, as I began to be drawn into his patter, I felt that Arindam was telling the rising Indian middle class a story about itself, offering them an answer to the question of who they were.

Chaudhuri, a

business man, business school founder, public speaker, entrepreneur, Bentley

owner and global consultant—among other things—was outraged when Deb’s book was

completed. He has since sued for defamation, insisting that the chapter about

him is inaccurate and tainting. Quite creatively, Deb tells us, he has filed an

injunction in Silchur, a dot of a city in Assam in north-eastern India,

hundreds of miles away from the courts, publishing houses and newspapers of

Delhi. Not only has Chaudhuri taken great pains to travel this far to file a

lawsuit for Rs. 500 million, but he is filing it against four parties:

Siddhartha Deb, Penguin Publishers, Caravan Magazine (that printed an excerpt

from Deb’s book featuring—or exposing—Chaudhuri) and Google India!

Deb deadpans

that Google India’s probably auto fills the word ‘fraud’ when someone types

‘Arindam Chaudhuri’ into the search bar, and this must make Chaudhuri very

angry.

Anger is

prevalent throughout the book, not surprisingly, as Deb talks to the

marginalized, the invisible, the unpaid, the evicted, the toiling, the cheated,

the rip-offs and the jaded. In the final section featuring a north-eastern girl

working as a waitress in Delhi, the anger matures into gritty determination and

hard-earned independence. Esther (not her real name) is optimistic about making

a life for herself in a metropolis, but she tires of the superficial,

ultimately inaccessible, glitz of her job in food and beverages (F&B) The

redundancy of routine and responsibility wear her down.

‘I feel like a thief,’ she said. ‘When I come home, everyone’s sleeping. It’s a strange job that requires you to be up when everyone else is in bed.’

Esther’s section

is sympathetic and admiring, prompting the reader to wonder, did Deb get more

involved with her than with his other characters? The moderator says that many

reviewers have suggested a romantic relationship, which Deb corrects: “One!”

Gesturing

animatedly, Deb insists that there was no romance: his sole aim was to

“dissolve the boundaries between the observed.”

These days Esther spoke differently about her job. ‘I wanted to be a doctor, not this F&B. Sometimes, I want to go back home, but what is there back home? If I go home, what will I do? But this job has no security, no pension.’…what Esther sometimes wanted, after all her independence, striving, exposure and mobility was a simple repetition of her mother’s life.

Questions follow

his reading. Deb advocates for his narrator, who is “pretty angry and pretty

skeptical about what he’s seeing.” This first-person narrator is a microphone

for his characters, for the four years of research he has done all over the

subcontinent. “I am not pretending to be objective,” he says.

Deb defends his

preference for fiction over non-fiction. “I actually prefer the novel as a form,”

he explains, but thought initially that non-fiction would be more effective for

such a subject. He thought it would be quicker, too, and that he would “make a

ton of money, come back to fiction.” So much for that, he laughs. “Here I am, six years later!”

Deb defends his

preference for fiction over non-fiction. “I actually prefer the novel as a form,”

he explains, but thought initially that non-fiction would be more effective for

such a subject. He thought it would be quicker, too, and that he would “make a

ton of money, come back to fiction.” So much for that, he laughs. “Here I am, six years later!”

When asked about

the seamless transitions between characters, villages and personal

contemplations, Deb describes the tiring, painstaking attention to detail a

writer must have, especially since it yields richer, truer stories. “A lot of

the shaping happens in the writing as well,” he says—the mark of a practiced

and accomplished writer.

Writing a book

of such ambitious scope takes commitment, curiosity and, ultimately, a profound

need to capture the world in your own words. “If you hit it,” he promises, “it’s

the most transcendent thing. It comes alive.”