So here we are: arms sore with copies of Franzen’s Freedom (and, I begrudge the audience, Lahiri’s Unaccustomed Earth) we want signed, eyes sore from scanning the auditorium for empty seats and drawing near blanks. Wilsey gamely welcomes the audience and explains the importance of libraries, and libraries for children. He quotes Jorge Luis Borges—a librarian as well as a writer—whose words I must include here, because he is tremendous:

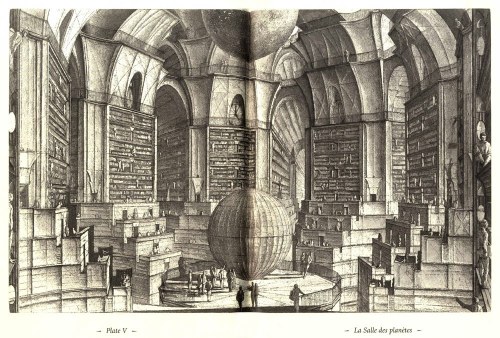

Like all men of the Library, I have traveled in my youth; I have wandered in search of a book, perhaps the catalogue of catalogues; now that my eyes can hardly decipher what I write, I am preparing to die just a few leagues from the hexagon in which I was born. Once I am dead, there will be no lack of pious hands to throw me over the railing; my grave will be the fathomless air; my body will sink endlessly and decay and dissolve in the wind generated by the fall, which is infinite. I say that the Library is unending. The idealists argue that the hexagonal rooms are a necessary form of absolute space or, at least, of our intuition of space. They reason that a triangular or pentagonal room is inconceivable. (The mystics claim that their ecstasy reveals to them a circular chamber containing a great circular book, whose spine is continuous and which follows the complete circle of the walls; but their testimony is suspect; their words, obscure. This cyclical book is God.) Let it suffice now for me to repeat the classic dictum: The Library is a sphere whose exact center is any one of its hexagons and whose circumference is inaccessible.

Like all men of the Library, I have traveled in my youth; I have wandered in search of a book, perhaps the catalogue of catalogues; now that my eyes can hardly decipher what I write, I am preparing to die just a few leagues from the hexagon in which I was born. Once I am dead, there will be no lack of pious hands to throw me over the railing; my grave will be the fathomless air; my body will sink endlessly and decay and dissolve in the wind generated by the fall, which is infinite. I say that the Library is unending. The idealists argue that the hexagonal rooms are a necessary form of absolute space or, at least, of our intuition of space. They reason that a triangular or pentagonal room is inconceivable. (The mystics claim that their ecstasy reveals to them a circular chamber containing a great circular book, whose spine is continuous and which follows the complete circle of the walls; but their testimony is suspect; their words, obscure. This cyclical book is God.) Let it suffice now for me to repeat the classic dictum: The Library is a sphere whose exact center is any one of its hexagons and whose circumference is inaccessible.

Moderator Sean Wilsey, initially overwhelmed by Lahiri and Franzen’s entries in his anthology State by State, confesses to us that his praise for their pieces was received with more sedated emails from them: “you really need to try to reign in your hyperbole.” But his child’s kindergarten teacher need not, he assures us in his introduction that is anchored in the glory of libraries and literacy (hence Borges earlier). She is teaching her students the alphabet—specifically, the “spatial relationship of lower case letters”—and “baby j,” for example, “dips its feet in the water and likes to play ball.” Creativity, humor and word-making have no bounds—like Borges' library.

Time for the authors to indulge us and themselves a little. Lahiri goes first. She is precise at  the microphone, holding her manuscript up firmly. She inflects such that each clause ends on a minor note, hooking lugubriously onto the next. Her excerpt is from a novel-in-progress: two urchins who have stolen onto a golf course in their hometown of Calcutta where they marvel at its manicured elitism, its “perfect little [golf ball] holes like navels in the earth.” These are boys whose youth unabashedly drives their subconscious into smorgasbords of adventure, so that they have to “[step] so many mornings out of dreams.” Another character compares the colors outside her window to the jars of Indian spices on the sill; very clever.

the microphone, holding her manuscript up firmly. She inflects such that each clause ends on a minor note, hooking lugubriously onto the next. Her excerpt is from a novel-in-progress: two urchins who have stolen onto a golf course in their hometown of Calcutta where they marvel at its manicured elitism, its “perfect little [golf ball] holes like navels in the earth.” These are boys whose youth unabashedly drives their subconscious into smorgasbords of adventure, so that they have to “[step] so many mornings out of dreams.” Another character compares the colors outside her window to the jars of Indian spices on the sill; very clever.

“The Mediterranean,” he begins, “is nothing but extremely blue.” He is stooped over the mic, having not adjusted it after Lahiri, and looks casually at the audience, naturally lifting his eyes off the page to talk to us (I don’t mean to compare him and Lahiri, but I shall anyway). He doesn’t just frame a precise picture with poise—usually authors read only enough to give us an outline—but tells us a story easily, informally. However this is nonfiction, and after a sip of water, he dramatically unplugs a flow of facts about birds damned to extinction, and we are both amused and informed. “There ensued a blur of fighting,” he writes of a group of men confused in their confrontation. One character’s fanaticism is “matter-of-fact,” and so is Franzen when he looks up to tell us that “it’s just really stupid” to hunt migratory birds in the Spring when they’re off to reproduce. Later he can’t tell if a bird meat’s bitterness is “real or the product of emotion.”

“The Mediterranean,” he begins, “is nothing but extremely blue.” He is stooped over the mic, having not adjusted it after Lahiri, and looks casually at the audience, naturally lifting his eyes off the page to talk to us (I don’t mean to compare him and Lahiri, but I shall anyway). He doesn’t just frame a precise picture with poise—usually authors read only enough to give us an outline—but tells us a story easily, informally. However this is nonfiction, and after a sip of water, he dramatically unplugs a flow of facts about birds damned to extinction, and we are both amused and informed. “There ensued a blur of fighting,” he writes of a group of men confused in their confrontation. One character’s fanaticism is “matter-of-fact,” and so is Franzen when he looks up to tell us that “it’s just really stupid” to hunt migratory birds in the Spring when they’re off to reproduce. Later he can’t tell if a bird meat’s bitterness is “real or the product of emotion.”

Back to Wilsey to address questions of his own and from the audience to the authors sitting on either side of him, and he is utter unpreparedness is visible in the boy’s smirk across his face. Franzen responds with witty impatience, masterfully trading words for silence, lost in thoughts and gazes before speaking. Stalling humorously, Wilsey circuitously asks the authors about geography. Franzen talks of investing his characters—often Midwestern—with “explanatory power to make life more interesting…our own watered down version of myth.” Lahiri says that geography “is increasing for me as a preoccupation of work.”

In the case of Fiction v. Non-Fiction, Franzen argues that Non Fiction is “playing the game of writing, waiting for something to happen,” whereas fiction “seems somewhat indulgent” since the author gets “really involved in stuff you’ve made up”. But he is clearly an author since he finds “straight up journalism...incredibly confining.”One Brooklyn Waldorf parent to another, Wilsey asks Lahiri about kids. She advocate reliving childhood through them since it’s “nourishing to question things, struggle with things.” Fiction writers are “repeatedly decoding the world, an unsolvable puzzle,” as parents do for their children.

Paradoxically, Franzen claims to hates research and Lahiri believes that when writing there is “some sort of research going on continuously to create a life through language.” Franzen teaches us that when Kafka wrote Amerika (aka The Man Who Disappeared) set in Oklahoma, “Oklahoma was just a word he knew.” He thinks for a moment. “I don’t think he did too much research on bugs either.”

PS. Happy Birthday, Anusha!

No comments:

Post a Comment