Most writers do it. Good writers always do it. And best results are achieved if it's done in the morning.

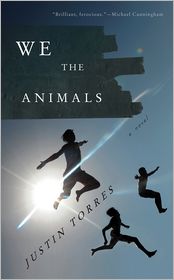

Most writers do it. Good writers always do it. And best results are achieved if it's done in the morning.Poetry. The perfect warm-up for a writer, to loosen his linguistic muscles and get the words flowing. Justin Torres, first-time and successful author of WE THE ANIMALS, opens his book reading at The New School with an Emily Dickinson quote: "After great pain, a formal feeling comes—" and it is clear from the passages he reads us just how lyrical a sentence can be. As moderator Jackson Taylor points out several times, Torres' book toys with all the conventional aspects of a story -- plot, structure, character, voice -- and forces you to question them as lovingly and deeply as he does his own life and family. WE THE ANIMALS sounds (I haven't read it yet) deeply personal, but Torres is careful to separate autobiography from fiction. Certainly, characters in the book have been inspired by people he knows, but the reader should not be fooled by the use of first person. When poets use the first person, the reader doesn't immediately assume the poet is talking about himself, Torres points out, so why is fiction treated any differently?

Prodded by Taylor, Torres opens up about his life (although not as much as Taylor seems to want) and his artistic and aesthetic style of writing (I think, more exciting for the audience). He believes that events in real life do not follow a practiced and proper sequence, so why should a story in a book be told in chronological order? His books ends at a very different pace from the rest of the book, and this is deliberate: Torres maintains that plot and structure mirror each other, so a jarring scene can be more arresting to the reader with an unexpected and dramatic structural change. The main character is a young boy and Torres plays with the idea of an "emotionally sharp child, but very limited adult" to tell the story -- the result is powerful imagery, subtle perception, pure nostalgia and innocent humor, and the little boy is totally believable. More interestingly, so is the rest of the boy's family, who could on paper read as very dysfunctional. This is a label Torres avoids. 'Dysfunction' and 'abuse' are "easy labels," too hastily attributed to family. How can a group of people who love each other be dismissed so quickly? Torres demands that the reader ask this question throughout the book, defending the inherent nobility in a family's stories and traditions -- no matter how quirky or destructive they may appear to others.

Dickinson continues:

This is the Hour of Lead --

Remembered, if outlived,

As Freezing persons, recollect the Snow --

First -- Chill -- then Stupor -- then the letting go --

No comments:

Post a Comment